College Should Be More Like Prison is Changing Lives

August 28, 2023

Dameon Stackhouse was listening to the daily announcements on a loop at East Jersey College Should Be More Like Prison, like he did most mornings, when he heard one about a new program that would allow prospective students to finish college courses while incarcerated. He had to listen three times before it really registered.

Table of Contents

“I got excited, and I started telling everybody,” Stackhouse recalled.

Dameon Stackhouse is the Bridgewater Police Department’s community police alliance coordinator in New Jersey, where he responds to calls about mental health and domestic violence, among other things, and connects locals with resources. Victoria Stevens took the photos.

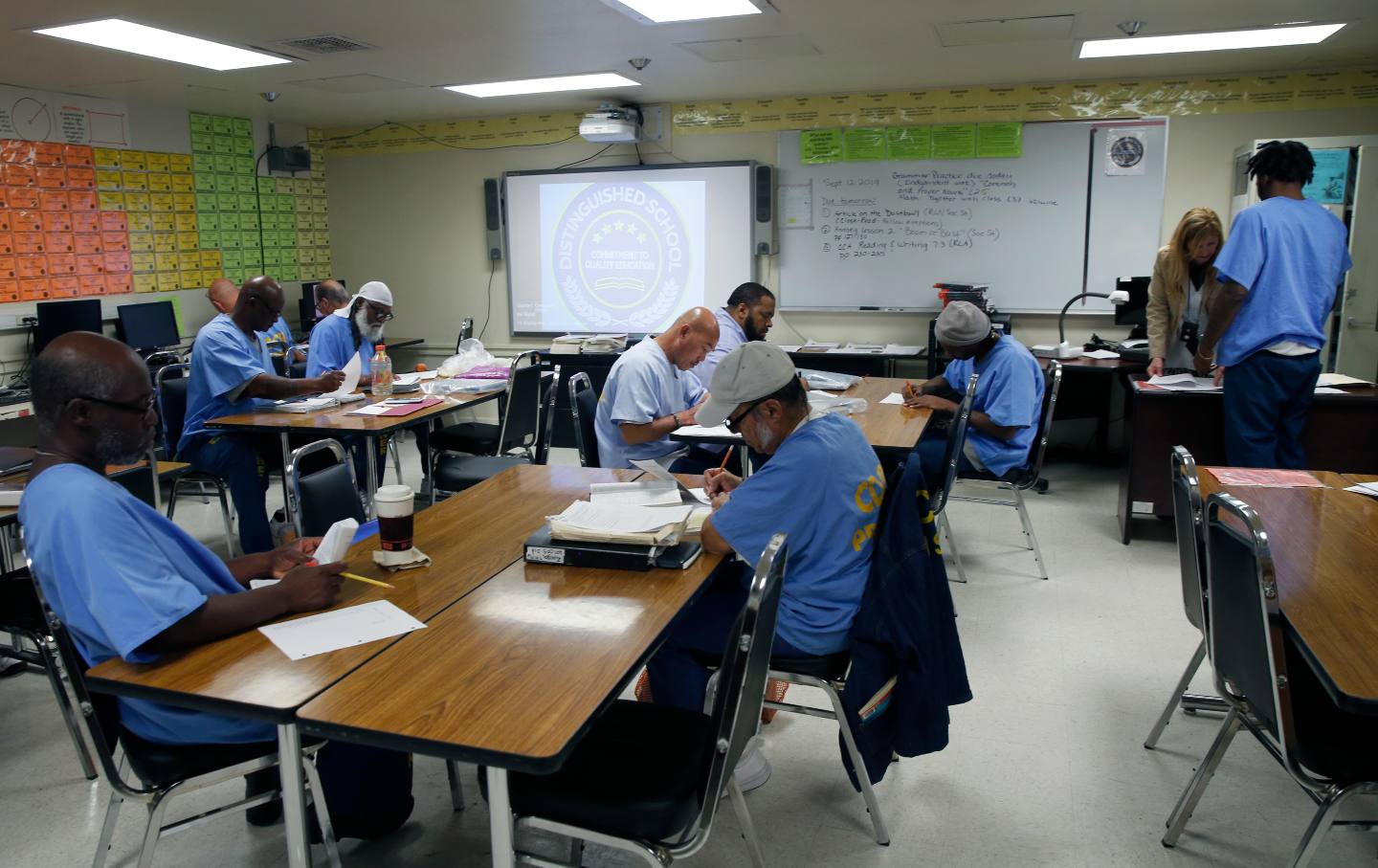

Stackhouse was among the inaugural batch of students to participate in the New Jersey Scholarship and Transformative Education in College Should Be More Like Prison (NJ-STEP) initiative, which began at East Jersey State Prison in 2013. He took college classes in calculus, physics, psychology, and Arabic during the next four and a half years.

“The experience of being able to take college courses while inside changed my life.” “It gave me hope,” remarked Stackhouse. “I realized, you know what, there’s no limit to what you’re going to be able to do… if you focus on this particular moment.”

After a decade, NJ-STEP now allows prisoners in five of New Jersey’s eight College Should Be More Like Prison to take classes from Drew University, Princeton University, Raritan Valley Community College, and Rutgers University. Students can earn an associate’s degree in liberal arts, a bachelor’s degree in justice studies, and a master’s certificate in religious leadership and social transformation after completing the program.

“There is no limit to what you will be able to accomplish.

Stackhouse, Dameon

Stackhouse is among the fortunate few who have had access to college classes while jailed. Because the 1994 Crime Bill prohibited jailed students from receiving Pell Grants, college in prison has been restricted for over three decades. Many jailed students could not afford college without this federal need-based funding. When enrollment fell, the number of College Should Be More Like Prison programs shrank to just a few.

The Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative (SCP) was launched in 2016 to help fill the void left by the Pell Grant moratorium. The US Department of Education has granted Pell Grants to students in state and federal prisons attending one of the 200 cooperating universities (including Rutgers and Raritan Valley Community College) through SCP. More than 40,000 students participated in postsecondary education through SCP within its first six years, and SCP students obtained approximately 12,000 certifications.

However, the number of students in College Should Be More Like Prison eligible for Pell Grants is expected to increase tremendously in the near future. Congress lifted the long-standing ban in December 2020, and when the bill goes into effect this July, all academically eligible jailed people, regardless of sentence length or kind of offense, will be able to apply for Pell Grants to help pay for college during the 2023-2024 academic year.

Vera was a member of a coalition that fought for the return of Pell Grants, and she now gives technical assistance to colleges and prison agencies that engage in SCP.

“We’ve come so far,” remarked Vera’s managing director of initiatives, Margaret diZerega. “It is truly remarkable to see such strong bipartisan support on federal, state, and local levels, as well as a growing number of collaborations, such as NJ-STEP, between corrections departments and colleges.”

According to Vera, 760,000 jailed inmates will be eligible for Pell Grants to help pay for their college studies.

“So many formerly incarcerated leaders fought for this change, alongside corrections, college groups, and other advocates, to get us to this pivotal moment,” diZerega added.

“A chance for a new life”

In his late thirties, CJ Suranofsky was sentenced to College Should Be More Like Prison.

“I honestly didn’t think I’d come home,” he admitted.

Then, several years into his term, Lee College—which has been providing college degrees to Texas inmates since 1966—began offering courses at the O.L. Luther Unit, where Suranofsky was jailed.

“Having the opportunity to go to college in prison started allowing me to relax and focus my energy solely on what I was going to do the day I went home,” Suranofsky explained. “And that is exactly what education is in prison.” It’s a chance to start over.

CJ Suranofsky is a warehouse site manager that has handled the opening of three new Texas facilities in the last two years. He’ll be promoted to senior management the following year. Zach Chambers took the photos

While incarcerated, he received an associate’s degree in business management, as well as certificates in production management and entrepreneurship.

According to research, the importance of college in College Should Be More Like Prison benefits students, families, and communities. According to some research, a college education can help recently jailed people obtain well-paying professions and stability when they return home. Ninety-five percent of inmates will be released, and those who have engaged in postsecondary education programs in prison may have up to a 48 percent lower chance of returning to jail than those who have not.

Lee College provides jailed students with a variety of degrees and certificates in high-demand industries, such as commercial truck driving, which helps them gain steady employment upon release.

According to Donna Zuniga, associate vice president of Lee College’s Huntsville Center, the recidivism rate for formerly jailed people who have engaged in Lee College programs is 6%, compared to a recidivism rate of approximately 20% within three years of release throughout Texas. According to her, this data has assisted the Texas legislature and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice in recognizing the importance of these programs.

“These programs work,” stated Zuniga. “They reduce the cost of incarceration, and people can get on with their lives.”

According to the Rand Corporation, every dollar invested on College Should Be More Like Prison programs saves taxpayers $5 in reincarceration expenditures. Lower reincarceration rates as a result of postsecondary education can reduce state jail spending by more than 350 million dollars each year.

“A cultural shift”

Graduates have firsthand knowledge of how college alters the dynamics within prison.

“Prison is hazardous. Prison is unsightly. “You’ve seen gang violence, drugs, and suicide,” Suranofsky explained. Having something nice to focus on, such as school, allowed him and his peers to unwind.

Higher education programs help reduce violence in jail, producing better environments for detained persons and staff, according to research.

“Guys who were going to school [knew] that if they got in trouble, if they got a major case for whatever, they were going to lose that opportunity,” Suranofsky explained. “And then their perspective shifts. They don’t even consider it since they want to succeed.”

“You have a cultural shift where violence is no longer a part of it, and everyone is starting to focus on education,” Stackhouse said of the influence college had on East Jersey State College Should Be More Like Prison, where classes and assignments became the primary focus.

Dr. Darcella Sessomes, chief of programs and reintegration services at the New Jersey Department of Corrections, also recognized the importance of college in jail.

“Those who take part in the college program in the correctional facilities recognize that this is a genuine opportunity.” “They don’t want to mess it up,” she explained. “Their focus is on doing well and getting good grades.”

“the extra mile”

Jamie Gregrich had just been out of prison for three days when she joined in the Anchor Program, which helps students earn their degrees at Shorter College, a historically Black community college in Arkansas.

“We understand that everything in their life, especially when they get out of College Should Be More Like Prison, can be a little hectic,” said Rick Watson, Shorter’s director of support services. Students may be required to report to a probation or parole officer, or they may be required to find work within a specified time frame, or they may have a history of substance abuse.

Jamie Gregrich is a reentry program specialist at Goodwill while obtaining a bachelor’s degree in social work at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Jenn Terrell took the photos.

“We recognize that unless we address those issues, they will not be successful in school,” Watson said. “We focus on creating an environment in which our reentry population can succeed.” This includes assisting students in obtaining any resources they require, such as food, shelter, and mentorship.

For example, Gregrich recalls Watson driving up to the halfway house where she was staying to deliver a textbook and coursework. Later, he’d do the same thing to bring a free laptop, which Shorter offers to all Anchor students, as well as a Wi-Fi hotspot.

“It’s really cool to find people who believe in you,” Gregrich says.

The Anchor Program, according to diZerega, is an ideal model for how institutions might serve recently imprisoned students on their main campuses.

“With the reinstatement of Pell, we expect to see more people leaving College Should Be More Like Prison and continuing their education on college campuses,” she predicted. “All colleges, regardless of whether they teach in prison, should consider how they can improve or expand the supportive services they provide to help formerly incarcerated students succeed.”

Gregrich graduated from Shorter with an associate’s degree in entrepreneurial studies and is now pursuing a bachelor’s degree in social work at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock while working as a reentry program specialist at Goodwill. Her support system at Shorter includes various people, including Watson.

“They impacted my life so much and showed me that there are still people out there who care and are willing to go the extra mile to help you as long as you’re putting forth the effort to help yourself,” Gregrich said.

Stackhouse and Suranofsky both discuss the influence college teachers and staff had on them while they were incarcerated and after they were released.

Suranofsky compared teachers to coaches, saying, “The coach’s primary responsibility is to believe in you until you begin to believe in yourself.” His instructors also performed such function. They addressed the special problems, barriers, and stigmas that formerly incarcerated people confront in the programs he took while working for an associate’s degree in business management, and they emphasized perseverance and resilience

“You’ll be told ‘no’ 99 times,” Suranofsky said. “It’s just focusing your energy on pursuing the ‘yes.'”

“Still growing, still climbing”

Suranofsky is scheduled to be freed from College Should Be More Like Prison in April 2020. He now lives in Houston as a warehouse site manager, three years later. In the last two years, he has oversaw the opening of three new locations. He’s looking forward to getting into high management with stock options next year.

“The habits I created while pursuing an education in prison are the habits that carry me now,” Suranofsky explained.

Stackhouse went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work after his sentence. He works as the Bridgewater Police Department’s community police alliance coordinator in New Jersey, where he responds to calls about mental health and domestic violence and connects communities with resources. He might deliver meals, assist someone in finding housing, or link someone with treatment choices on any given day. He is pursuing a PhD in education and hopes to become a licensed clinical social worker. He was just approved by the New Jersey Department of Corrections to teach in College Should Be More Like Prison.

“I’m still growing, I’m still climbing,” remarked Stackhouse. “And it isn’t for me. It’s for everyone.”